|

Follow @melhoshy

Loading

|

|

Sinai is a truly magical place and, as an Egyptian, I find it distressing that we continue to marginalize the Bedouin population of the region...

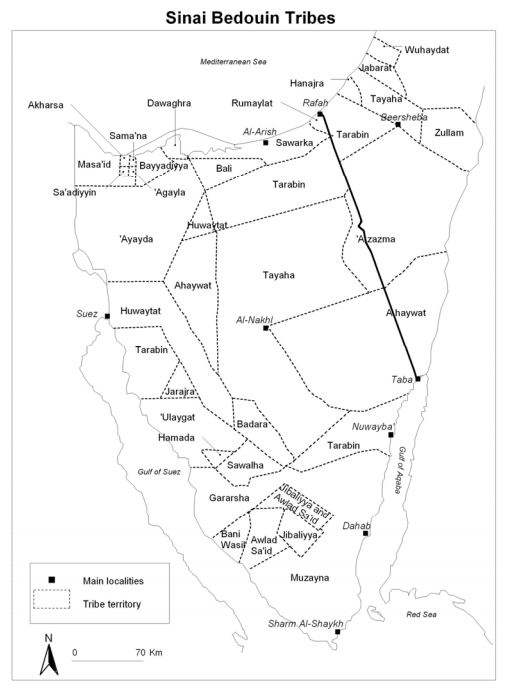

As with any ethnic population, their demands are simply to be respected and to be allowed to thrive on their own land... Moreover, I have been told countless times by various Bedouins that they yearn for the Egyptian government to be inclusive, to provide them with opportunities and to stop oppressing them and their culture... I am personally slightly partial to the Muzayna tribe, just given my experience, but I've heard from many that they have had pleasant experiences across the peninsula/tribes.. |

Great in-depth article on Egypt's Bedouins in Sinai

Jack Shenker article (@hackneylad) article link http://www.jackshenker.net/egypt/band-of-outsiders.html with some interesting excerpts below

- “In the minds of Egyptians we are just stereotypes: drug dealers, criminals, agents of Israel. I think us and the Egyptian state... we are just two entities that don’t understand each other."

- The government’s approach to the Bedouins of Sinai has not only bypassed a genuinely appealing cultural attraction for foreign visitors, but has also created a powder-keg that threatens to plunge the Peninsula into turmoil. And yet the state’s fears of disloyalty are misplaced. They have certainly succeeded in turning the native population against the government but, despite the fullfrontal assault on their livelihoods and heritage, every single Bedouin I spoke with declared their pride at being an Egyptian. “The state wants to assimilate the sons of tribes into mainstream ‘Egyptian culture’, and I don’t even know what that is,” says Khalil Sawarka. “But our problem is not with Egyptian society.” Sayeed Atiyid, from Beir Shabana, agrees. “Yes, we face poverty and discrimination,” he tells me. “But people here feel 200% Egyptian. That’s all there is to it.” As Sinai’s remarkable story of growth and change continues to play out, it remains to be seen whether these proud Egyptians can secure any place for themselves in the Peninsula’s uncertain future

- Authoritarian and politically unstable, the Egyptian government is busy consigning one of its most vibrant minorities to the shadows, fearful that their different way of life and complex patterns of identity could undermine loyalty to the state.

- “They had so many dreams,” smiles Sayeed as he shows me round the village, referring to his parents’ excitement at the Israeli withdrawal. “They weren’t expecting reforms and development from the Israelis,” explains the 26-year-old, “this was never Israel’s land. But they expected a future from the Egyptians – tourism, agriculture, industry, the utilisation of the land for the many, not the few. They expected wrong.

- “If there was something else, anything else...” he trails off, before gesturing dismissively in the direction of Sheikh Zwayd, the nearest town. “But the factories get all their workers from Cairo, they’re closed to me. Everyone my age is bored, sick of the government and sick of sitting at home. There’s nothing to do.

- Despite the presence of major olive oil, gas and cement plants on its fringes, the town’s Bedouin natives suffer a staggering 90 per cent unemployment rate. There is no lack of jobs at these industrial facilities, but they go to the legions of Nile Valley workers who have been aggressively resettled in Sinai by the government.

- But as an independent report by the International Crisis Group in 2007 documented, the state has “systematically favoured” the Nile Valley migrants while “discriminating against the local populations in jobs and housing”. For evidence one need look no farther than Fayrouz, a much-hyped regeneration project on Sheikh Zwayd’s beachfront initiated after the Israeli withdrawal, designed to provide business opportunities to local Bedouins and still cited in Egyptian education manuals as a symbol of Sinai’s enlightened development. The problem is that it doesn’t exist: the sweeping seaside promenade that was supposed to be a magnet for new hotels and restaurants is blocked off to the public and guarded by an armed policeman

- In the days after the Taba bombing over 3,000 Bedouins were rounded up and imprisoned without charge; according to Human Rights Watch several were tortured and had family members kidnapped by the police in an effort to extract confessions. Among the detainees were war heroes once feted for their resistance to the Israelis in the 1960s and 1970s

- Percentage of Sharm El Sheikh's developed land for Bedouin use by 2017: 1.6%

- Last April two young Bedouins on a motorbike had the temerity to overtake a security vehicle on a motorway, an act that left them both dead in a hail of police bullets. Neither were suspects in any crime and no warning shots were fired. The prosecutor’s office investigated the case but opted to bring no charges against the policemen responsible.

- The Egyptian government claims that it needs an extensive security apparatus in the area to combat high levels of illegal activity among the Bedouins, including the trafficking of goods in and out of Israel and Gaza. The smuggling problem is real: sex workers, commodities and weapons move one way, and drugs and money flow in the opposite direction. But it’s doubtful the Egyptian security forces have stemmed the tide; if anything, it seems that local police tacitly facilitate some parts of the trade in exchange for information that tightens their grip on local dissidents.

- Customary law, which the Bedouin tribes have long used to settle their differences, is being exploited by officials who offer select deals to tribal sheikhs, elders or other prominent community leaders – many of whom are now appointed by the government – and in return secure the obedience of the entire tribe. “Customary laws now have a purely political use,” explains Hefny. “The agreement struck between the police and prominent Bedouin leaders is that the latter are given carte blanche to do whatever they want, legitimate or not, and in return those leaders maintain political security and shut down any protests among their people.

- The next morning I travelled a few kilometres up the coast from Al Arish to inspect the front line of another battlefield. Here, on the fringes of the city, stands the brand new Sinai Heritage Museum, a slab of marble and glass that symbolises the energetic struggle being waged over Bedouin identity. Almost $10m was spent creating this cultural centre and funding excavations in the area – a worthy investment, to be sure, but the museum is focused almost entirely on Pharaonic history, a past of vital importance to the Nile Valley that nevertheless holds little relevance to Sinai. Beneath five floors of well-lit displays, the museum’s Bedouin heritage collection is consigned to a single basement room where the items on show – despite being impressive in beauty and range – lack any captions, in Arabic or English.

- The government’s project to “Egyptianise” the region extends to the neglect of local cultural identity: a programme manager at Cultnat, the Egyptian government’s centre for heritage preservation, told me that there was currently not a single state-sponsored project anywhere that involved Bedouin culture. “There’s no interest whatsoever,” he said. “I don’t know why.

- After buying a small plot from some fellow Bedouins he went to register it with the authorities, only to be told it already belonged to Americana, a vast restaurant and retailing multinational. “They said they would pay me a small salary to live on the land as a guard,” remembers Jomaa. “I told them I had paid for this land myself and would do what I wanted with it, but they told me no, we only give this land to companies, not individuals.” Jomaa’s dream – of a simple campsite on the beach – had no place in the bold corporate makeover of the coastline. Jomaa managed to register himself as a company to get around the TDA rules, but, he says, “the authorities looked at my proposals and said no, this is bad. The people in Cairo won’t like this at all. Where is the air-conditioning?” Jomaa went ahead and built his eco-friendly huts and solar-powered cooker anyway. Now the Ministry of Investment is demanding $10,000 for a lease, which he cannot produce. “So I am silent, and, for now, they are silent. But the day they come to take this land, to make it into another Marriott or Hilton, that will be the last day of my life. It will destroy me.

- With the partial construction of a concrete wall around the city to keep locals out, and the legal prohibition on Bedouins offering camel rides to tourists, international visitors can bask in the warm corporate glow of 91 high-end resorts, safely insulated from anything resembling traditional Bedouin life in the region. The dollars that pour into Sharm flow straight out of the Peninsula – at one five-star hotel every single one of the 250 employees comes from the Nile Valley and the only people now allowed to offer native-style “soirées” into the surrounding desert are official tour operators – a Bedouin experience, minus the Bedouin.